Largest San Jose school district kicks cops from campuses

San Jose CA June 27 2021

After nearly a yearlong debate, San Jose education leaders are booting police officers from San Jose Unified School District campuses—at least for the next school year.

The school board Thursday considered a contract between the district and the San Jose Police Department, along with a resolution to limit police officers’ involvement in student discipline and training to improve interactions with youth.

But after hours of heated testimony, the school board voted unanimously against the resolution and voted 3-2 against a new agreement with the police department for the 2021-22 school year. Board President Brian Wheatley and Trustee Wendi Mahaney-Gurahoo voted in favor of the agreement while Trustees Carla Collins, Teresa Castellanos and José Magaña opposed.

District Superintendent Nancy Albarrán made the news official in an email to parents Friday.

“Following their discussion, the Board of Education voted to end San Jose Unified’s partnership with the San Jose Police Department,” she wrote. “We understand the magnitude of this issue and recognize that this was not an easy decision to make, as evidenced by the 3-2 vote.”

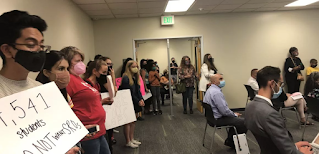

Parents, educators and activists flooded the Thursday meeting to urge the board to end the district’s relationship with police. Protesters gathered outside chanting and holding signs that read “Counselors not Cops” and “Schools not Prison.”

“Take that funding and spend it on the youth,” said Crystal Calhoun whose grandchildren attend school in the district. “We have more cops on campus than counselors and nurses. It’s time for us to take care of these children.”

Albarrán said police officers on campus helped provide “a range of services” to keep students, employees and schools safe from things such as illegal fireworks to supporting students who were assaulted. Her administration recommended continuing the partnership with police, with a caveat that officers are not involved in student discipline and receive specialized training.

She assured parents in her letter Friday that the schools still have “comprehensive” safety plans and training, despite losing officers on campuses. Some procedures for criminal activity on school campuses will need to be altered, she added.

“We will also need to determine how we will replace the range of supports school resource officers provided to both students and staff, and we will likely need to reduce or eliminate large-scale events for public safety purposes as law enforcement support will no longer be available,” she said.

SJUSD Superintendent Nancy Albarran said she found it difficult to balance her personal and professional feelings about having police on campus. Photo by Lorraine Gabbert.

Albarrán said Thursday she empathized with kids and families who had traumatic experiences with the law.

As a teenager, the superintendent said, she was pulled over in a truck by police and sat down on the sidewalk with a flashlight in her face.

“As a Latina, I have brothers, I have a father, I have uncles who have had less than positive experience with law enforcement,” Albarrán recalled during the meeting. “As a child growing up in poverty with a father that would have been pulled over and doesn’t speak English, I know what that feels like.”

Wheatley initially worried about the triggering aspect of students seeing police on campus, but said he was “in a different place” after speaking with parents and seeing a resolution to limit officers’ involvement with school discipline.

“If we continued with the same (school resource officer) program we’ve had in the past, I was not going to support that,” he said.

Mahaney-Gurahoo asked for additional training around special education and mental health. She said principals, kids and parents she spoke with wanted to keep officers on campus.

“My son is a boy of color, and my husband is a man of color,” she said. “They did start talking about the national picture and what it’s like… being around police. This conversation isn’t easy for me, either. My constituents want (officers).”

But Magaña said the original intent of having cops on campus was to build community—and the impact didn’t match the intent. He said students of color, those with disabilities and low-income students faced disproportionately higher rates of interaction with police on campus.

“To me this is disconcerting,” Magaña said. “I cannot support an MOU with the (school resource officer) language included.”

The San Jose Unified Equity Coalition hosted a rally at the district headquarters ahead of the meeting. The group has led the effort to remove police off campuses since last June.

“The purpose of schools is for our next generation to realize their potential,” local organizer Mary Celestin said. “I do not picture cops there with guns and with punitive approaches, who not only make students feel unsafe but also criminalize them.”

Castellanos said many students did not feel safe with police on campus, but recommended creating a safety-related task force. She suggested the district call community service officers when needed rather than hire officers. With the money saved from severing the police contract, she suggested bringing more mental health services to schools.

“This is the beginning of a conversation,” Castellanos said, “not the end of a conversation.”

San Jose Unified School District, the largest in the city with 28,000 students, is not the first to remove law enforcement from school campuses.

The Alum Rock and the East Side Union High School districts last year voted unanimously to remove San Jose police officers from their campuses.